Tales of the Inn

Each post here will share a single story — a glimpse into the life of someone who passed through The New Inn over the years. These are imagined guests inspired by fragments of real history, woven with warmth, character, and a touch of mystery.

The Shoemaker’s Fingers – 1854

Set during a bitter Helm Wind season in the Pennines

They’d warned me about the Helm Wind — said it could flay a man’s cheeks and make the trees creak like they were begging for mercy. I’d never felt anything like it till that spring. Sharp as a file and loud as judgement.

I was walking east out of Alston with a bundle of boot leather wrapped in sackcloth. Thought I’d cut through Dufton to call on a widow who still owed me for a pair of laced half-boots. Snow still clung to the fell like it hadn’t got the message that winter was done.

By the time I reached The New Inn, I couldn’t feel three of my fingers. They were blue at the tips. I pushed the door open and near fell into the fire.

The landlord was a stout man with no patience for nonsense and a heart of gold under it. He took one look at my hands and barked for his daughter to fetch the mustard tin and boiled cloth. Said she’d saved more fingers than any doctor south of Penrith.

They wrapped my hands and fed me broth thick enough to stand a spoon in. Outside, the Helm Wind howled like it was looking for someone to carry off. Inside, a shepherd recited folk cures while a travelling preacher argued with the brewer about predestination. It was warm, and real, and kind.

My fingers healed stiff. Can’t work a fine stitch these days, but I get by. I left behind a pair of half-finished brogues on the hearthstone. I heard someone hung them over the bar — stiff as wood now, but still holding shape.

Like the land. Like the people.

— Edwin Bragg, Shoemaker of Brampton

Historical Note

The Helm Wind is a fierce, cold easterly wind unique to the Pennines — especially near Great Dun Fell and the Eden Valley. Locals in the 1800s feared it for its icy sharpness, roaring noise, and sudden onset. It could bring snow in April, damage crops, and leave skin chapped raw.

In the 1850s, much of the Eden and Westmorland area lived in deep rural poverty. Farming was hard, trade was slow, and many survived on barter, craft, and community resilience. Inns like The New Inn offered more than warmth — they were lifelines.

The Old War Hat – 1782

A tale told by a discharged dragoon, late of the King’s army

I’d seen blood at Saratoga and mud in Durham. Had a scar on my neck from an officer’s ring and powder burns on both sleeves. When they discharged me, I didn’t go home — truth is, I didn’t know where that was anymore. Just pointed myself west and walked till my boots cracked.

That’s how I came to The New Inn. The sky was weeping and the Helm Wind had teeth. Inside was warm, dark, and low-beamed, with a fire that crackled like musket shot.

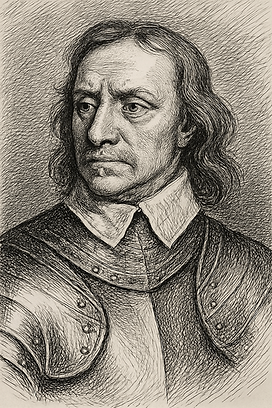

There was a man by the hearth wearing a three-cornered hat so battered it looked older than the building. He said he’d fought at Dunbar — with Cromwell, no less. Claimed he was a boy drummer then, now retired to walk the fells and stir pots with his walking stick.

I didn’t believe him, not fully. But the way he told it — the rain in his voice, the rhythm of it — I couldn’t look away. He said Cromwell once slept beneath a broken cart near Appleby, wrapped in a stolen horse blanket and quoting Scripture to no one in particular.

We drank until the shadows leaned in. He gave me a tip for dressing wounds with ale and burnt wool. I gave him a silver button from my old jacket. He tucked it into his boot and called it payment for the story.

Might’ve been mad. Might’ve been telling the truth. Doesn’t matter. I remember the sound of the fire, the weight of the dark, and how the wind couldn’t get in that night.

— Isaac Marran, Dragoon, Discharged

Historical Notes

-

By the 1780s, many British soldiers were returning from the American War of Independence — some wounded, some aimless, all altered.

-

The Helm Wind continued to torment the Eden Valley with its strange, roaring gales, recorded frequently in journals of the time.

-

Tales of Oliver Cromwell’s campaigns were still told in taverns, sometimes by those who’d actually served — often by those who hadn’t but made good drama of it.

The White Mare – 1799

A tale retold from the old road between Appleby and Dufton

It was late autumn, and the trees along the beck were stripped bare like old ribs. I'd left Appleby just after midday, aiming to make Dufton by dark, though the light was already slipping. I'd stayed at The New Inn — warm broth, good fire — and the innkeeper warned me before I left:

"Don’t cross the open ground if the Helm starts to stir. She rides early some years."

I thought he meant a shepherd's warning, wind or rain maybe. But somewhere between Battlebarrow and the rise before Dufton Ghyll, the air changed. The silence wasn’t peaceful — it was the kind that presses on your chest.

That’s when I saw her.

At the edge of the lane — pale, still, and staring. A white mare. No rider. Not tethered. Just watching. Then she turned off the track and walked straight into the rough grass below Dufton Pike.

My packhorse stopped dead. Refused to move. I stepped down, planning to lead it past, but the mare was gone. Only the grass stirred.

When I reached Dufton, the locals weren’t surprised. They said others had seen her — some before bad weather, others before worse things. One man told me she was once a traveller lost in a snow squall a hundred years ago, still searching for the road.

I stayed the night and returned to The New Inn the next morning, shaken and grateful. The wind rose behind me, dragging clouds down from Great Dun Fell.

They say the Helm Wind screams across these fells when it has something to say. I still wonder if that white mare was warning me… or leading someone else away.